Rewind, back to summer 2018. Buckling under the glare of the Netflix cameras, the heat from Cyril Abiteboul’s yellow submarines, and the demise of what was once his prized asset, Gunther Steiner had a tough decision to make. He was hanging over the eject button, beads of sweat heavy enough to fall and depress the thing theirselves, all the while Romain Grosjean waited for the decision.

He was ultimately spared by his boss, thanks to an 11th hour renaissance giving Haas the support they needed in the points tally, but one year on it’s a case of deja vu. Only this time, the situation’s different. Being bested by his teammate Kevin Magnussen again in the standings is one thing, but the two have been drawn like magnets to each other’s carbon fibre, and team morale is at an all-time low. The American dream could well be over for Romain.

If that button’s finally pressed, it’d be easy to think the jig is up for him in F1 entirely. What team’s even in a position to take on a 33 year old with a history of erratic form, radio outbursts and, if his current partnership is anything to go by, struggles with maintaining morale with his other side of the garage? Well, there is still one chapter potentially left in his book of tales: Alfa Romeo.

Before I delve any deeper, there’s a majestically-haired elephant in the room in Antonio Giovinazzi. Youthful rookie and Ferrari academy product, the natural assumption is that he’s safe for 2020. Even I think that, though there’s every chance Alfa could start to take a dimmer view of his potential if his results fail to pick up by the season’s end. So far 32 of the team’s 33 points have been scored by their talisman Kimi Raikkonen, with Antonio contributing a sole point, while the qualifying battle is 7-4 in the Finn’s favour.

This doesn’t tell the whole story. After his two-race cameo at the beginning of 2017, Antonio went 23 months without competitive racing – which has brought on an understandable rustiness to his craft – and has shown flashes of what made him such a formidable force in GP2 three years ago. Also, while he may be in the twilight of his career, Kimi’s shown no signs of hitting the brakes, driving like a man reborn throughout the season. Antonio’s results aren’t as black and white as they appear.

Serious questions will arise if he doesn’t improve in time for post-season though, and in an ever-sharpening midgrid slog Alfa need a much more even split of the points if they want to trouble the upper places in the Constructors’ table. Ferrari’s commitment to treating him as a genuine contender for a future race seat of theirs’ could evaporate too, what with Mick Schumacher waiting in the wings and the Scud suffering with the absence of a man who performed admirably in their simulator department.

If those results don’t come, and both Ferrari and their understudies decide Antonio is best placed back on the sidelines, there stands two options. Do they wait for Mick, and hope he can jump the final barrier to the big time? Or do they reach out for an experienced hand, and give the next scarlet prodigy time to find his feet? Mick himself has never been one to rush his progress, and his carefulness has worked so far. The latter stands as the best option.

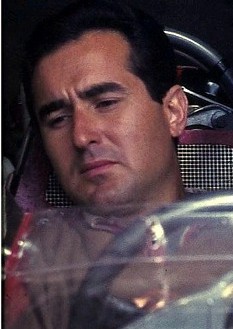

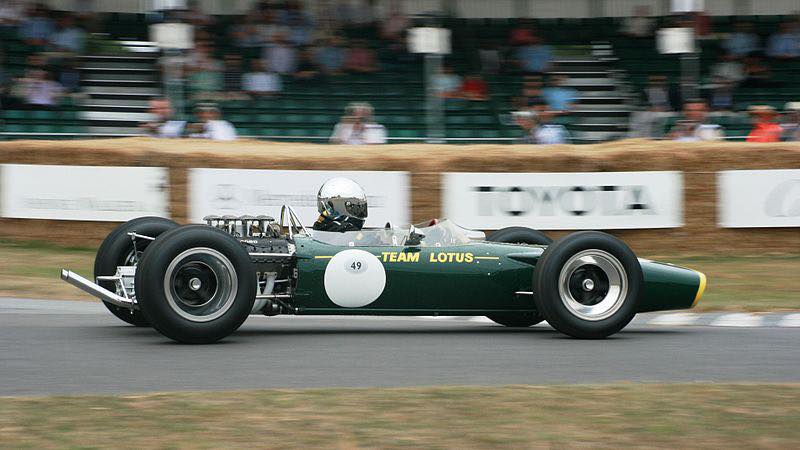

Romain could become the most desirable free agent on their radar, if Steiner finally calls time, and despite the many flaws in his arsenal there’s benefits to a team like Alfa having him onboard. Firstly, those teammate issues I talked about? They won’t have them. Not only is Kimi arguably the most docile and unproblematic driver they could hope for, he’s also well aware of Romain after their two seasons together at Lotus in 2012 and 2013, when they worked fairly harmoniously as a duo. No red flags to be found there.

Alfa Romeo’s a harmonious team to be at in general, too. Romain’s a confidence player, and when he’s made to feel comfortable he’s undoubtedly capable of contributing star races for his team – he’s shown that at Haas in the past and especially with his against-the-odds podium in Belgium 2015 – so the lack of pressure in Switzerland would suit him down to the ground.

It’s also too frequently forgotten just how blazingly quick Romain is. The second half to his 2013 season was a comeback for the ages, with him acting as the only real threat to Red Bull and taking four podiums in his final six races. His aforementioned podium with Lotus in 2015, against the backdrop of financial woes and even bailiffs hounding the team, was a much-needed bright light in their season. His first season with Haas resulted in a beatdown of Esteban Gutierrez, with the team’s 29 point haul entirely down to him. He’s more than capable of hitting those heights again, given a fresh start.

The final reason the move makes sense is that Kimi won’t keep going forever. Alfa have gained immeasurably from having a sage head within their driver line-up, but once his contract’s up at the end of 2020 that’s likely to be his final contribution to the sport. Bedding in a like-for-like replacement in Romain, while Mick plies his trade once more in F2, would mean that when he’s finally prepared for the step up they have a known quantity alongside him – a strategy which has worked so effectively this season.

If there’s any team that can get a tune out of Romain, it’s Alfa Romeo. And if there’s anyone who can fill the brief Alfa will need when Kimi hangs up his overalls, it’s Romain. Antonio still has the greatest claim to their second seat, but if he were to be deemed surplus to requirements, there’s a golden chance to plan for the future by recreating a flagging driver’s past.